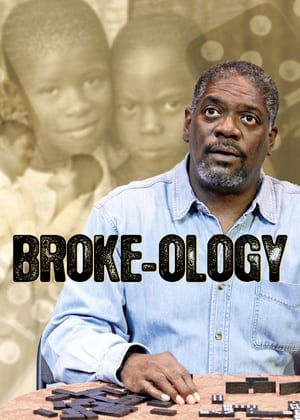

On one level, you could call Nathan Louis Jackson’s “Broke-olgy, an “urban“ drama—urban being the common euphemism for: having to do with ethnic minorities who don’t have much money. Its characters the Kings are an African American family of few means living in a Kansas City ghetto. “Broke-ology” does not however focus its lens, as you might expect, on issues of inequality or racial identity politics. At its heart this moving play is about coping with loss and with aging.

This is not to say that poverty and racial identity aren’t prominently addressed. Ennis, the elder of the two King brothers, (played at the Lyric by David Curtis), praises himself as a “pimp.” He struggles to be a good husband to his often-anxious wife and a strong role model to his young child while suffering the humiliations of a poorly paid fast food employee. His younger brother Malcolm, played by Monty Cole, has the opportunity to leave the ghetto behind for a position at the University of Connecticut and Ennis views the potential move as an act of betrayal. “Broke-ology” in fact, refers to Ennis’ attempt to show his academic brother that negotiating ghetto life is as complex a science as any that could be taught.

Certainly though, Malcolm’s painful decision about whether to stay in the limited world of his family or else leave to pursue his own dreams transcends race and class. It’s a very common conflict in art because it’s the defining choice in the lives of most artists. The same decision was faced by a Hasidic Jew who longed to be a painter, in the Lyric’s most recent drama, “My Name is Asher Lev,” and it’s the central conflict of one of the most produced, celebrated and studied dramas in the history of American Theater: Arthur Miller’s Glass Menagerie.

Beyond this conflict though, the heart of “Broke-ology” is the story of William, Ennis and Malcolm’s father, played with great pathos and sensitivity by Johnny Lee Davenport. William prematurely loses his wife Sonia, portrayed with both grace and realism by Patrice Jean-Baptiste. He never comes to terms with this loss and his devastation is exacerbated in his old age, as more losses pile up. Illness and wear are causing him to lose his physical and his mental facilities, and now he may even be losing the aid and comfort of his ambitious youngest son. Watching Davenport’s William struggle to parent his sons as they struggle with each other over who will shoulder the burden of keeping him alive, is as heart-rending and cathartic an experience as you are likely to have in a theater.

There are plenty of lighthearted moments built into “Borke-ology as well. Mny of these surround the theft of a garden gnome from a neighbor’s yard, which turns into William’s friend, confident and dance partner. The Lyric’s production struggles with these moments, however, or at least did so in its opening weekend. The King family’s laughter in the aftermath of their gnome-heist, or during their repartee over games of dominos, felt forced. While individually excellent the cast never quite synched up their rhythms. Davenport’s habit of filling silences with mumbles and stutters, might have contributed to the challenge. I wondered too about the briskness with which the play’s unsettling ending was dispatched.

I hope these actors will hit their groove as a unit over the course of the run. Their talent and their work is evident in the power they to bring to the more somber notes of this worthwhile drama—a study not just of living with poverty but with everything important in life that breaks down.

Directed by Benny Soto Ambush, “Broke-ology” plays through April 23.

Leave a Reply