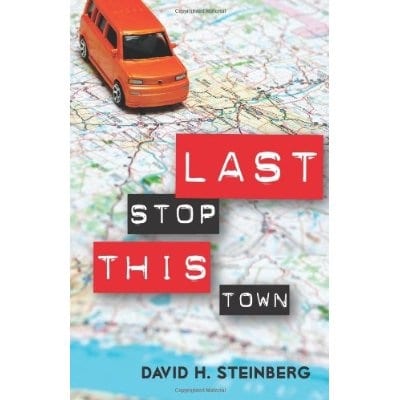

Given its April 6th debut, there’s a good chance most diehard “American Pie” fans have already seen “American Reunion” by now. If this latest slice left you craving second helpings, never fear. Screenwriter David H. Steinberg recently penned a novel. “Last Stop This Town” follows high school seniors Dylan, Noah, Pike and Walker as they spend their days drag racing down residential suburban streets, bribing homeless guys to buy them beer, and signing yearbooks at pathetic house parties. When Dylan suggests they live up their last weekend of high school at an underground rave in New York, the guys are ready to go crazy and make memories for the ages. Chock full of Steinberg’s signature humor, “Last Stop This Town” should be enough to tide you over between now and the premiere of “American Midlife Crisis.” Here, the writer talks process, poop humor, and why your story won’t go anywhere if you can’t develop characters that make people care.

Given its April 6th debut, there’s a good chance most diehard “American Pie” fans have already seen “American Reunion” by now. If this latest slice left you craving second helpings, never fear. Screenwriter David H. Steinberg recently penned a novel. “Last Stop This Town” follows high school seniors Dylan, Noah, Pike and Walker as they spend their days drag racing down residential suburban streets, bribing homeless guys to buy them beer, and signing yearbooks at pathetic house parties. When Dylan suggests they live up their last weekend of high school at an underground rave in New York, the guys are ready to go crazy and make memories for the ages. Chock full of Steinberg’s signature humor, “Last Stop This Town” should be enough to tide you over between now and the premiere of “American Midlife Crisis.” Here, the writer talks process, poop humor, and why your story won’t go anywhere if you can’t develop characters that make people care.

BLAST: What draws you to coming of age stories? Did you have a particularly interesting coming of age yourself?

DAVID H. STEINBERG: I actually left high school after my junior year to go to college and I’m sure a psychologist would say that writing in the teen genre is my way of filling in the gap in my teenage experience. But I think there’s something more to it than that. It’s just a magical time. Those high school years are the time in everyone’s life when the flood of emotions and surging hormones makes everything seem so important and dramatic and you go through a million highs and lows every day. It’s a time when you really feel alive, and that’s something really cool and unique. Of course, there’s something to be said for those feelings subsiding as an adult and living without the daily drama, but for me, I actually loved that feeling of being invincible, that everything was possible, and that my whole life was still ahead of me. That youthful optimism (and maybe a bit of naiveté) is really what “Last Stop” is all about, as the four friends are about to graduate and go off into the unknown. But it’s also a book about homeless dudes throwing poop at you, so don’t let me pretend this is “Catcher in the Rye.”

BLAST: Which came first: the characters or the plot?

DS: It’s really all about the characters. Once you breathe life into them and know them intimately, then the plot unfolds because that’s what these guys would do. It’s like your vacation pictures. No one cares about the shots of buildings—they only want to see the ones with you in front of the fountain–because people care about people. So I start with high school archetypes—the player, the monogamous guy, the guy who can’t get laid, and the stoner—and then try to build on this to create three dimensional characters. If I’ve done my job well, they become real and unique. Pike starts out as “the stoner” but winds up being a completely new and different take on the original archetype. Look at Spicolli from “Fast Time at Ridgemont High”—same archetype, totally different character.

BLAST: How long has this novel been in the works?

DS: I originally wrote it as a screenplay, then adapted it into a novel because I fell in love with my guys. Overall, the process took four years–not very fast considering it’s under 200 pages. But I have a day job writing and directing movies, so cut me some slack.

BLAST: Which character from your “American Pie” series would you most like to hang out with?

DS: Nadia, duh.

BLAST: Which to do you prefer to write: fiction or screenplays?

DS: It’s hard to choose. Writing for film is a pretty amazing gig. Watching a movie in a crowded theater, seeing your name flash on the screen, and hearing them laugh at your jokes—there’s really nothing that can compare to that. On the other hand, screenplays are like sonnets—the structure and formatting is very restrictive. Plus, when you’re done, other writers re-write you, the director puts his stamp on it, actors improvise, editors move things around—it’s a hugely collaborative medium. Sometimes that’s awesome when talented people “plus” the script and make the movie great. Sometimes it’s not so awesome. Novels are liberating stylistically. I can write what characters are thinking and feeling, and screenplays obviously can only contain moments that can be seen or heard onscreen. But really, it’s about flying solo. If you love or hate my movie, I’m not sure how to take it—I only wrote the screenplay. But the book is all on me.

BLAST: How does your process for writing fiction differ from writing screenplays?

DS: You want to know the biggest brain adjustment? Writing in the past tense! Screenplays are all present tense because it’s technically stage direction. (“Dylan picks up the yearbook,” not “picked up the yearbook.”) But on a less mundane level, it’s really all the same. Create the characters and outline. Months and months of outlining. Write a draft really quickly, then months and months of re-writing.

BLAST: You’ve gotten a lot of praise for penning raunchy scenes that are also somehow sweet. How do you manage to walk this line?

DS: I have to own the raunchy humor, but the truth is I’m all about the drama and emotion of teenagers going through this traumatic time in their lives. Look at the “American Pie” movie posters. “American Pie 2” was literally just a picture of the ten characters standing there, doing nothing, because the marketing department knew that audiences care about characters, not the specifics of the raunchy humor. I think movies that try to “out-gross” each other without giving us characters to root for ultimately fail because they’re hollow experiences. Look at “Project X.” Sure, it’s funny and crazy, but the characters are unlikeable and no one goes through any sort of relatable life moment. So at the end of the day, who cares?

Now I know there are definitely critical people out there who will think this sounds pretentious and self-aggrandizing because really, I’m a guy who wrote this book where a homeless guy throws poop at people. But for me, it’s about four high school kids going to desperate measures to get beer for a party. Without the characters and the universally relatable situation and emotion, the poop joke isn’t funny. So ultimately, yes, I’m writing some very lowbrow material here, but I’m always also trying to say something worthwhile about the experience of being a teenager.

Leave a Reply