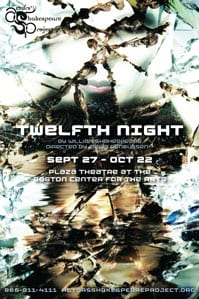

Bottom to Top: James Andreassi as Sir Toby, Steven Barkhimer as Feste, and Doug Lockwood as Sir Andrew. Photo by Stratton McCrady.

The best thing about ASP’s fresh take on Shakespeare’s most beloved festive gender-bender is that they take this comedy just a little bit seriously. The strongest example is the production’s version of Sir Toby Belch, the drunken uncle to the countess Olivia, who torments his niece’s butler, sleeps with her serving maid, throws raging all night parties in her kitchen and sends an idiotic suitor to woo her, simply for his own amusement.

Sir Toby is often played as a beer-bellied, blustering, buffoon. In this production, the role goes to James Andreassi, whom ASP featured as Marc Antony, in last season’s closer, “Antony and Cleopatra.” On a physical level, Andreassi looks like he’s ready to strap the armor back on at any moment. While his antics are funny, they don’t feel free-spirited. They feel heavy-spirited. His outsized appetites and his roguishness are endearing, but always just a little bit scary. When he gets backed into a corner that just a little becomes quite a bit.

Before seeing Andreassi’s performance, it had never occurred to me how much Sir. Toby can be seen as a darker, less decorous version of the play’s Duke Orsino. Orsino, played in this production by Jason Bowen, whom ASP last cast as Othello, spends the play wallowing in the passion of his unrequited love for Olivia, who is too busy stewing in her own grief for her recently deceased brother to entertain his entreaties.

Duke Orsino is the speaker of the famous lines, “If music be the food of love, play on/Give me excess of it; that surfeiting,/The appetite may sicken, and so die.” It turns out that his appetite sickens, and so dies, just one line later. Orsino may lack Toby’s affinity for mischief making, but he is an equal in the extremes of his unquenchable desires and in his tendency toward dramatic mood swings. Just like Toby, when it looks like the doom is sealed on having his will, he threatens violence. In Bowen’s performance, the threat is half-hearted, and perhaps this is right; From Orsino, it’s just another show of melodrama.

Sir Toby’s foil, Malvolio, Olivia’s puritanical steward, is another character who is often played a bit cartoonishly off the bat. ASP artistic director Allyn Burrows is hilarious in the role but he’s also refreshingly understated. You can tell Burrows has “found his clown.” Burrows is trim, fastidious and composed and you can imagine this wonderfully anal Malvolio, as a stretched-out version of him in is worst moments. He starts as a believable enough busy body with a proverbial rod up his derrière. Once a trick played by Sir Toby and his compatriots gives makes him drunk with imagined power, he wriggles and squirms like a child who’s had fruit loops for breakfast.

Paula Langton is wonderful as Maria, Malvolio’s underling, whose cleverness in tormenting her boss is rewarded with love and worship from Toby and friends. Sparks fly between this Toby and Maria from the first time they share the stage and Langdon’s Maria, like Andreassi’s Toby, manages to be likeable while also betraying a real sinister streak. They can be hilarious in toying with the defenseless twit, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, played as a sympathetic simpleton by Doug Lockwood.

They’ve got a pretty formidable posse as well, with Gabriel Graez as an impish Fabian, leading the charge in gulling Malvolio one minute and bowing and scraping before the Duke, the next, and the very talented character actor, Stephen Barkhimer as Feste, the traveling musician and comedian.

Barkhimer’s mysterious, trench-coated Feste is in some ways, a good step ahead of the pack. Unlike everyone else, he knows that Viola, our romantic heroine, is in fact a woman, even if he doesn’t know why she is serving Duke Orsino in drag. He knows how to make Olivia crack a smile in the depth of her despair and how to make the self-serious Duke Orsino pay him for a jest. He knows when it’s safe to join Toby’s crowd and when its best to shuffle out of the picture. But for all of his cleverness, there is a sadness to him and even a bit of pathos. As a lowly entertainer, he is in many ways impotent. He must duel with Malvolio for influence over their mistress and despite some attraction, he knows he can’t vie for her hand.

Mara Sidmore, a perpetually insightful actor, delivers as Olivia. Her pale skin and fierce blue eyes blaze forth from a jet black dress of mourning as she does her best to clench onto the safety of her grief despite a whirlwind of excitement: her uncle’s antics, her servant’s madness, her jester’s jokes and, the one thing she cannot resist, the presence of the Caesario, Viola’s male alter ego, made in the image of Sebastian, the twin brother she believes has drowned.

Marrianna Balsham’s Viola isn’t a scene a stealer. She is a laid-back go-between who brings out the extremes in her scene-mates in the way they react to her cool wit. With her even-keeled alto and floppy shoulder-length coif, she’s a bit reminiscent of Keanu Reeves. It’s a very fresh take on Viola, and the most celebrated Viola lines trip nonchalantly off her tongue as new inventions.

Director Melia Bensussen takes a few liberties in the structure of the play and some of them pay off. She helps to clarify the story of the play, for example, by reversing the order of its first two scenes.

A less canny choice is her strange device of giving disguised Viola several of her twin brother Sebastian’s scenes, with Sebastian skulking spectrally in the background. Eventually, I decided that I was supposed to suspend my disbelief and see Sebastian in her place, and that this was supposed to help trick me into seeing them as identical. This was a difficult leap to make. The moments were confusing, and puzzling over them pulled me right out of the story by which I’d been so effectively held.

Bensussen also chooses to end the play by having its cast join Feste in his final song. The song turns out to be a melancholy dirge. It’s a strange note to end on. These experiments are forgivable offenses. By and large this Twelfth is rich, insightful, and funny.

“Twelfth Night” plays at the Boston Center for the Arts’ Plaza Theater through October 22.

Your insightful review of Actors’ Shakespeare Project’s “Twelfth Night” is an excellent journalistic record of what may be an important production for how it may correct an audience’s view of this rhapsodic and erotic play too long distorted by theater companies such as Trinity Rep, which set its 2010 “Twelfth Night” during a raucous Twelfth Night celebration (there is no mention of the holiday Twelfth Night in the play) at a dilapidated gentlemen’s club as an excuse to pack the play with gimmicks and turn what is essentially a dark and sexual comedy into a farce comedy. “Twelfth Night” is not an early, two-dimensional Shakespeare play such as “The Comedy of Errors” and “The Two Gentlemen of Verona.” Shakespeare may have redeployed the separated identical twins and a cross-dressing heroine plot devices from his earlier comedies in “Twelfth Night,” but this time he used them in a far more sophisticated and devious manner to launch sexual identity crises among the principal characters as a result of Viola’s decision to become “Cesario.” The unsettling sexual desires her actions trigger are far from sorted out at the play’s end, in which monogamous relationships for Olivia, Sebastian, Viola and Orsino seem very unlikely. The mistake that many directors make when staging “Twelfth Night” is that they look back to early Shakespeare comedy rather than at the darkly sexual plays—“Hamlet,” “Troilus and Cressida,” “Othello,” “Measure for Measure,” “All’s Well That Ends Well” and “King Lear”—that surround “Twelfth Night.” It is, in fact, not a regurgitation of early Shakespeare comedy, but rather the gateway play to Shakespeare’s sexually-darkest plays, written amid the Shakespearean zenith and a stellar part of an unbroken string of masterworks from “Hamlet” to “Anthony and Cleopatra.” Wayne Myers, author, “The Book of Twelfth Night, or What You Will: Musings on Shakespeare’s Most Wonderful (and Erotic) Play.”